[ad_1]

BBC

BBCFive occasions Prof Kevin Fong broke down in tears in a nondescript listening to room in West London, whereas giving proof to the Covid inquiry.

The 53-year-old has the type of CV that makes you listen: a guide anaesthetist in London who additionally works for the air ambulance service and specialises in house drugs.

In 2020, as Covid unfold around the globe, he was seconded to NHS England and despatched out to the worst hit areas to assist different medics.

We’ve lengthy been instructed that hospitals were struggling to cope through the pandemic. In January 2021, then prime minister Boris Johnson warned the NHS was “under unprecedented pressure”.

But now many hours of testimony to the Covid inquiry this autumn is providing our clearest understanding but of what was actually occurring on the top of the pandemic.

The inquiry restarts its stay hearings this week with proof from medical doctors and affected person teams. Health ministers and senior NHS managers are additionally anticipated to seem earlier than the top of the yr.

I used to be on the inquiry the day Prof Fong calmly talked by means of greater than 40 visits he led to intensive care models, his voice cracking at occasions.

What Prof Fong found on the hospitals he visited was one thing he stated couldn’t be discovered in the official NHS information or the principle night information bulletins on the time.

“It really was like nothing else I’ve ever seen,” he stated.

“These people were used to seeing death but not on that scale, and not like that.”

In late 2020, for instance, he was despatched to a midsize district hospital someplace in England that was “bursting at the seams”.

This was simply because the second wave of Covid was hitting its peak. England was days away from its third nationwide lockdown. The first vaccines were being rolled out however not but in massive numbers.

In that hospital, he discovered the intensive care unit, the overflow areas and the respiratory wards all full with Covid sufferers.

The earlier night time somebody had died in an ambulance exterior ready to be admitted. The identical factor had occurred that morning.

The employees were “in total bits”. Some of the nurses were sporting grownup nappies or utilizing affected person commodes as a result of there wasn’t time for lavatory breaks.

One instructed him: “It was overwhelming, the things we would normally do to help people didn’t work. It was too much.”

That night time, Prof Fong and his workforce helped to switch 17 critically ailing sufferers to different NHS websites – an emergency measure unheard of outdoor the pandemic.

“It is the closest I have ever seen a hospital to being in a state of operational collapse,” he stated.

“It was just a scene from hell.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe full story

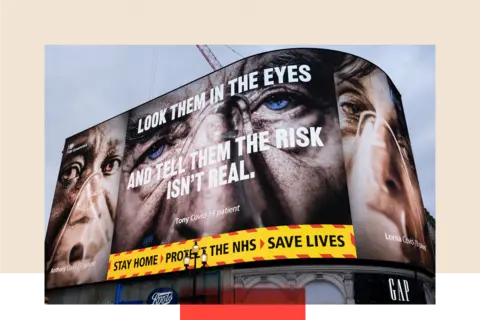

In the pandemic we heard reviews of swamped hospitals in hazard of being overwhelmed although to what extent was by no means totally clear.

On the face of it mattress occupancy in England – that’s the overall variety of hospital beds taken up by all sufferers – didn’t hit greater than 90% in January 2021, the height of the biggest Covid wave.

That’s above the 85% degree thought of protected however not any increased than a typical winter exterior the pandemic.

That doesn’t inform the complete story. At that time hospitals had cancelled all their standard deliberate work – from hip replacements to hernia repairs. Strict Covid guidelines meant the general public were instructed to keep at dwelling and shield the NHS. The numbers coming in by means of A&E in England fell by virtually 40% in contrast to the earlier yr, to 1.3 million in January 2021.

That was why, when anti-lockdown protestors sneaked into hospitals to movie, they discovered abandoned corridors and rows of empty seats.

The strain although was usually being felt elsewhere – on the principle wards and in intensive care models (ICUs), the place hundreds of the sickest Covid sufferers wanted assist to breathe on ventilators.

“At our peak we ran out of physical bed spaces and had to resort to putting two patients into one space,” one ICU nurse at a special hospital instructed Prof Fong.

“Patients were dying daily, bad news was being broken over the phone or via an iPad.”

Later research by the Intensive Care Society found that in January 2021, 6,099 ICU beds were filled across the UK, well above the pre-Covid capacity of 3,848.

This huge spike in demand, equivalent to building another 141 entire intensive care units, was being driven by the length of time Covid patients needed treatment.

On average they would spend 16 days in ICU, normally on a ventilator, compared with just four to seven days for a patient admitted for another reason.

Surge capacity

As a result, hospitals had to rush to convert operating theatres, side rooms or other wards into makeshift intensive care units. NHS trusts often ended up juggling shortages of equipment, medicines and oxygen.

But while it might have been possible to cram in more beds, finding the extra skilled workers to staff them was far more difficult.

Prof Charlotte Summers, who led the intensive care team at Addenbrooke’s hospital in Cambridge, said: “We can’t just magic up specialist care staff because it takes a good couple of years, at least, for minimum critical care speciality training.”

“What we had, we had, and we had to stretch further and further.”

As a result staffing ratios were pushed to the limit in Covid, something she said politicians, the media and the public didn’t fully understand at the time.

Outside of a pandemic, specialist critical care nurses would be responsible for just a single patient. In Covid they were looking after four, five or even six – often all on a ventilator.

“Staff didn’t have time to process or accept the losses,” the lead ICU matron at one large teaching hospital told Prof Fong.

“As soon as one patient had passed away they had to get the bed cleared and ready for the next patient.”

Others in intensive care and Covid wards – from doctors to pharmacists to dietitians – saw their workloads stretched well beyond normal safe levels.

This was the main reason why temporary Nightingale hospitals, built in the first Covid wave at a cost of more than £500m, only ever treated a handful of patients. It was possible to build the critical care infrastructure almost overnight, but quite another thing to find trained medics to work in them.

To help plug these staff shortages in ICU, volunteers were frequently brought in from other parts of the hospital, often with no experience of intensive care medicine or of dealing with that level of trauma and death.

“They were being exposed to things which they wouldn’t necessarily be [exposed to] in their normal jobs, people deteriorating and dying in front of them, the emotional distress of that,” stated Dr Ganesh Suntharalingam, an ICU physician and former president of the Intensive Care Society.

Another hospital physician stated he felt some junior members of employees were “thrown in at the deep end” with little coaching and no selection about the place they were despatched.

The inquiry heard that every one this “inevitably” had an affect on a few of the sickest sufferers.

At no level did the NHS have to impose a proper ‘national triage’, the place somebody was refused therapy as a result of they may not get a hospital mattress.

But utilizing that as measure of well being system collapse could also be too simplistic anyway.

Prof Summers stated it could be mistake to consider “catastrophic failure” as a swap that goes “from everything being okay to everything not being okay the next second.”

“It is in the dilution of a million and one tiny little things, particularly in intensive care.”

She stated when the system turns into so overstretched it looks like “we are failing our patients” and never offering the care “that we would want for our own families”.

New analysis suggests these hospital models beneath the best strain additionally noticed the best mortality charges for each Covid and non-Covid instances.

Difficult choices were having to be made about which of the sickest sufferers to transfer up to intensive care.

Those Covid sufferers who wanted CPAP, a type of pressurised oxygen assist, reasonably than a ventilator, usually had to be cared for in basic wards as a substitute, the place employees could have been much less used to the know-how.

One nameless ICU physician in Wales stated: “We did not have sufficient house to ‘give people a go’ who had a very remote chance of getting better. If we had had more capacity, we might have been in a position to try.”

The inquiry was also told that at least one NHS trust was under so much pressure it implemented a blanket “do-not-resuscitate order” at the height of the pandemic. If a patient went into cardiac arrest or stopped breathing, it would mean they should not be given chest compressions or defibrillation to try to save their life.

In normal times, that difficult decision should only be made after an individual clinical assessment, and a discussion with the patient or their family.

But Prof Jonathan Wyllie, ex-president of the Resuscitation Council, said he knew of one unnamed trust that put in place a blanket order based instead on age, condition and disability.

Groups representing bereaved families said they were horrified, adding it was “irrefutable evidence the NHS was overwhelmed”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAir ambulances

At times, the impact on intensive care was so great that some units had to undergo “rapid depressurisation” with dozens of patients transferred out, sometimes over long distances, to other hospitals.

Before the pandemic, from December 2019 to February 2020, only 68 of these capacity transfers had taken place in England. Between December 2020 and February 2021, 2,152 were needed, either by road or air ambulance.

Often it was the most stable patients in smaller district hospitals who would be selected for transfer as – bluntly – they were the most likely to survive in a moving vehicle for several hours.

“But what that meant for the smaller units is that they were left with a cohort of patients who were most likely to die,” said Prof Fong.

“Those units would experience mortality rates in excess of 70% in some cases.”

In normal times between 15% and 20% of ICU patients die in hospital, according to the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine.

Very human

Through the pandemic the NHS did continue to operate and, on a national basis, patients who really needed hospital treatment were not turned away.

But Prof Charlotte Summers, in her evidence, said staff are still “carrying the scars” of that time.

“You cannot see what we’ve seen, hear what we’ve heard, and do what we’ve had to do and be untouched by it,” she stated.

“You cannot and be human. And we are very much human.”

Health services in all four UK nations started the pandemic with the number of beds in ICU and staffing levels well below average compared to other rich countries.

Five years on and there are still almost 130,000 job vacancies in the NHS across the UK. Sickness rates among the 1.5 million NHS employees in England are running well above pre-pandemic levels, with days lost to stress, anxiety and mental illness rising from 371,000 in May 2019 to 562,000 in May 2024.

All this comes as the health service struggles to recover from Covid with waiting lists for surgery and other planned treatments still hovering near record levels.

“We coped, but only just,” said Prof Summers and Dr Suntharalingam in their evidence to the inquiry.

“We would have failed if the pandemic had doubled for even one more week, or if a higher proportion of the NHS workforce had fallen sick.

“It is crucial to understand how very close we came to a catastrophic failure of the healthcare system.”

With the inquiry ongoing none of the agencies are currently commenting.

Additional reporting and analysis by Yaya Egwaikhide

Top photo credit: Getty

BBC InDepth is the brand new dwelling on the web site and app for one of the best evaluation and experience from our prime journalists. Under a particular new model, we’ll deliver you contemporary views that problem assumptions, and deep reporting on the largest points to allow you to make sense of a fancy world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content material from throughout BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re beginning small however pondering massive, and we wish to know what you suppose – you may ship us your suggestions by clicking on the button beneath.

[ad_2]

Source hyperlink