[ad_1]

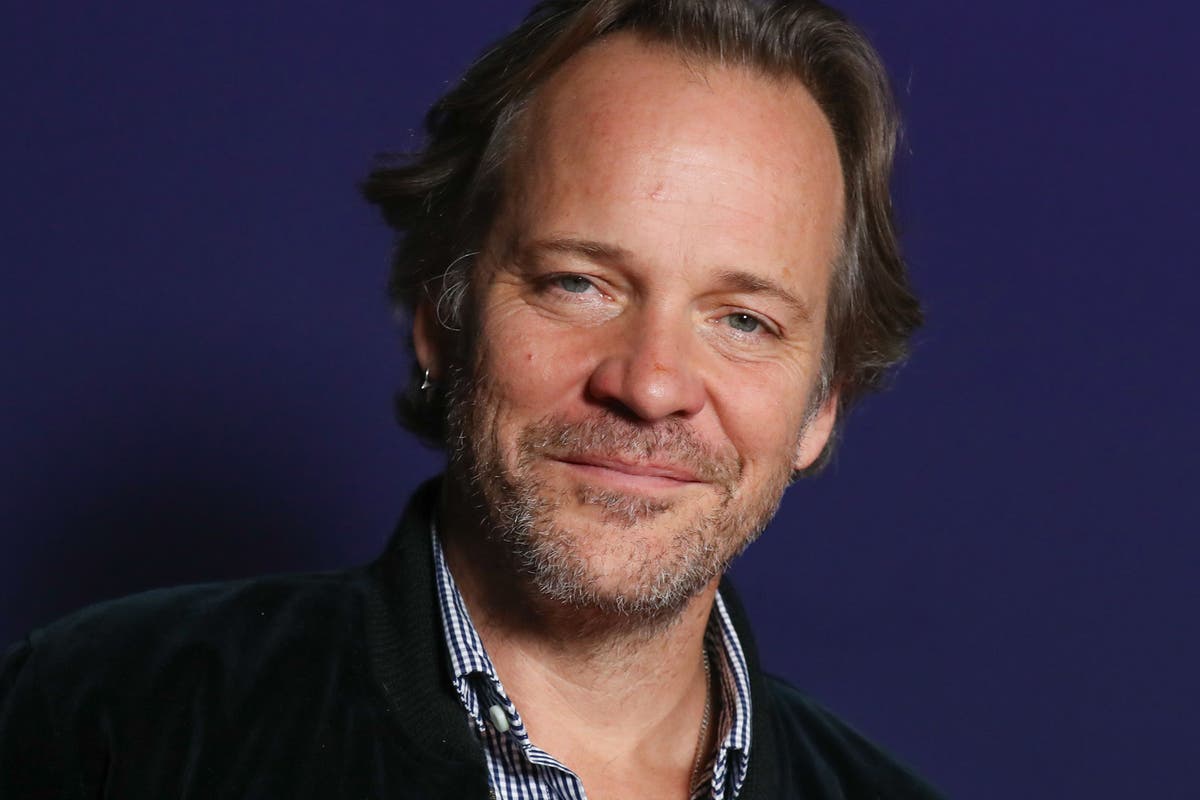

Trim and boyish-looking, the Emmy and Golden Globe-nominated actor Peter Sarsgaard has by no means had an issue with scenes involving intercourse, nudity or the busting of taboos. In the biopic Kinsey, he bared all and seduced Liam Neeson. In the psychological thriller The Dying Gaul, he was masturbated by Campbell Scott. For director Maggie Gyllenhaal – his real-life spouse – he humped a tree in the brief movie Penelope and slept with one of his college students in The Lost Daughter. “I’m such an object of desire in that movie,” he tells me from the research of his brownstone house in New York. “I couldn’t be more the object of desire!”

There’s full-frontal nudity in his new movie, too. Memory tells the story of Sylvia, a traumatised rape sufferer (performed by a clenched and gloriously un-glossy Jessica Chastain), who falls for Saul, a person with young-onset dementia. Sarsgaard is magnificent in the function, which received him the Volpi Cup for finest actor at final yr’s Venice Film Festival. And Memory, as a complete, is a triumph, one of probably the most edgy and uplifting films of the yr. Here’s what’s shocking: although Sarsgaard is blissful to strip, he’s insecure about his look. “I don’t love the way I look,” the 52-year-old tells me. “That’s true of many people. But I guess it’s unusual, since I’m an actor.”

He factors out that he’s nice watching Memory, though he says he’s “heavier” in it than he’s ever been, a outcome of an damage that left him unable to train for a couple of months earlier than filming. “I have all those disclaimers with this character, [so] I don’t mind the way I look in it.” He provides that it’s more durable for him when he’s taking part in a job in which a well-kept look is especially essential. “You know, where you’re supposed to look like Hugh Grant. Then all that stuff – the fretting – comes in. But luckily I don’t play a lot of characters like that. I don’t get that critical of how I look in films.” He sighs. “It’s more in life.”

Not that he’s given to self-pity. Sarsgaard’s spouse has been vocal about the best way ladies in Hollywood are always judged on their look, particularly as they strategy center age. He completely takes her level. Suddenly animated, he says, “I’m so thankful to be a man!” He explains how he and Gyllenhaal lately ran into an actor in her fifties. “I was standing there, just listening to Maggie and this woman talking about how difficult it is to be an actress getting older. That kind of thing is always eye-opening. As I’ve gotten older, the parts I’m offered have got more interesting. As a man, I take so much for granted.”

He’s delighted Gyllenhaal has discovered a manner to be seen inside the movie business. “I’m extremely proud of what my wife has done, which is to completely reinvent herself. Though, to anyone who knows her, it’s not actually a surprise.”

Gyllenhaal’s second function, The Bride, is an enormous Warner Bros-backed studio film that riffs on James Whale’s 1935 horror traditional Bride of Frankenstein. Also scripted by Gyllenhaal, it boasts an unimaginable solid that features Jessie Buckley, Christian Bale, Penelope Cruz and Annette Bening. Sarsgaard performs the detective trailing Frankenstein’s monster (Bale), his recently-created mate (Buckley) and possibly another person. There are rumours Buckley’s “bride” will couple up with Cruz’s character. But Sarsgaard received’t give something away. All he’ll say: “It’s this big, romantic, deeply romantic, wild, punk monster movie! I think it’s going to be energising! It’s rambunctious! People are going to be very surprised that this is Maggie’s second movie. It is nothing, at all, like The Lost Daughter.”

I have a necessity to know what’s going on with folks round me. It could be irritating to stay with me, really, as a result of I’m all the time spying in a method or one other

Gyllenhaal has paid tribute to Sarsgaard in the press, saying that whereas she filmed The Lost Daughter he took care of “the family side of things”, a uncommon instance of a person “gracefully, intelligently” supporting his companion. Do folks inform his spouse she’s fortunate to have him? He appears to be like incredulous. “I feel like I’m the one who’s lucky. Lucky to have Maggie! Because now I have my own director who’s gonna put me in her movies. I always wanted to work with someone over and over, making that relationship deeper and more interesting. I don’t think I’ve ever worked with the same director more than once. My wife is the only one!” So is that the plan? He’ll change into the Gena Rowlands to her John Cassavetes? “That sounds good! That sounds really good! Though I don’t know if The Bride is what you’d call a Cassavetes movie.”

When they’re at house, Sarsgaard and Gyllenhaal don’t talk about work. “We’re shooting The Bride at the start of April,” he says. “I know Maggie’s talking to some of the other actors in the movie, but she and I have almost said nothing. She just knows that’s not my way of working. I read a script a lot. Then I daydream about all the things that aren’t in it.”

An uncommon love story: Sarsgaard and Jessica Chastain in ‘Memory’

(Ketchup Entertainment)

He’s the sort of actor who thinks a script all the time has room for enchancment. When Sarsgaard reads one and sees a phrase like “he cries”, he’ll normally cross it out. “I’ll decide if I find something moving. You don’t get to tell me. You could do that with anyone. I’ll come up with something else!” He elaborates on a idea he’s clearly given thought to. “What someone writes on a piece of paper, in their apartment, has nothing to do, really, with what we do on the day… It’s very hard for a writer to fully invest in each character and give them their own point of view. That’s why you hire actors.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers solely. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews till cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers solely. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews till cancelled

Surely some filmmakers disagree? “Almost never,” he says, with a sly smile. “Because I come to the set with a positive attitude. I don’t verbalise anything. When they call action, I just start doing it my way. Then I listen to what the directors say, and try to incorporate it, or if it doesn’t make sense to me, I start working with them.” He’s positive administrators take pleasure in collaborating with him. “Michel Franco, who directed Memory, said the Spanish word for ‘script’ is ‘guide’.”

Sarsgaard is actually proud of Memory, a low-budget indie that, as he factors out a number of occasions, is a “tiny” challenge that few folks have to date seen (it’s solely made round $4,000 on the US field workplace). He’s conscious the time period “dementia” generally is a turn-off. “I frequently don’t even mention that word. When people ask me what Memory is about, I say, ‘It’s kind of an unusual love story.’ Which it is!” He praises Chastain for pushing so laborious to get the movie made (it was she who urged Franco to solid Sarsgaard). Asked to describe his co-star in one phrase, he opts for “direct”. What would she say about him? “Intuitive? I know that I’m very intuitive. That’s maybe my main skill.”

Object of need: Sarsgaard and Jessie Buckley in ‘The Lost Daughter’

(Netflix)

One of his favorite pastimes is people-watching. “I enjoy figuring out what the relationships are between people. I go to the park near here and I’ll think, ‘Father-daughter? Nope. Man and lover!’” He pulls a face. “Yeah, it can get weird. You don’t need to listen to the conversation. They say so little of the communication we do between us is verbal. I also like playing chess with strangers in the park. I like trying to read them.”

He thinks he began watching folks at a younger age. His father was an air drive engineer and the household moved rather a lot. “I didn’t talk very much. I was an only child, I didn’t have anyone to talk to! I was very quiet and still. So it might have been apparent that I was thinking about something other than video games.” Sarsgaard’s maternal grandfather, Phillip Reinhardt, “had the bearing of Robert Duvall or Tommy Lee Jones,” he says. “He was a very tough, Southern man; a mechanic at the fire station. And I was around him all the time and he said almost nothing. We hunted and fished. He’s the one who taught me how to play finger-style guitar. He used to play Mississippi John Hurt and Son House. A lot of African-American music. I felt like I knew him better than I knew anybody and yet I knew nothing about him. Nothing literal.”

Sarsgaard’s manner of interacting sounds intense. He nods. “I have a need to know what’s going on with people around me. It might be irritating to live with me, actually, because I’m always spying in one way or another, especially with my kids. I’m always thinking about them.”

Collaborators: Sarsgaard along with his spouse and frequent director Maggie Gyllenhaal

(Getty Images)

He and Gyllenhaal have two daughters, Ramona, 17, and Gloria, 11. Gloria sings and performs the violin, Ramona performs the oboe, accordion and double bass. Sarsgaard strikes the digicam so I can see the devices sitting in the nook of the room. “This is what I mainly do with my daughters. We have a little band.”

Sarsgaard’s research appears to be like immaculate. I inform him I interviewed Gyllenhaal when she was first beginning out, when she was selling the darkish comedy Secretary (2002). She gave me a chunk of recommendation: all the time make your mattress in the morning, as a “gift” to your self. Sarsgaard screws up his face. “That’s a great idea. Hmm… I’m thinking about whether or not our bed is made right now. I think the answer is probably.” He appears to be like over my shoulder, into my study-slash-bedroom and says, brightly, “I see that yours is!”

“You know what my advice would be?” he provides. “When you wake up, drink an entire glass of water. That’s helped me out. I think I walked around, dehydrated, for most of my life.”

Just as we’re about to say our goodbyes, Sarsgaard blows a kiss to somebody. It seems his canine, Babette, a wirehaired pointing griffon, is in the room. “Come here, baby!” Sarsgaard croons, earlier than scooping her up. She offers him a collection of ferocious licks earlier than he plops her again on the ground. As she trundles off, he shakes his head, fondly. “She’s a real sweetheart. She just wants to be with me all day long.”

Sarsgaard dotes on canine. And underdogs. In these troubled occasions, he’s simply the softie we want.

‘Memory’ is in cinemas from 23 February

[ad_2]

Source hyperlink