[ad_1]

Black and Asian people who spot cancer symptoms are taking twice as long to be diagnosed as white people, a surprising new examine exhibits.

Research by Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) and Shine Cancer Support exhibits that people from minority ethnic backgrounds face a mean of a 12 months’s delay between first noticing symptoms and receiving a prognosis of cancer.

These teams report extra unfavorable experiences of cancer care than white people, restricted information in regards to the ailments and lack of knowledge of help providers, which all contribute to later diagnostic charges.

“In a year that’s revealed that the UK’s cancer survival lags behind comparable countries, I am saddened but unsurprised that people from minority ethnic groups face additional hurdles that delay their diagnosis.” mentioned Ceinwen Giles, co-ceo of Shine Cancer Support.

“We know that catching cancer earlier saves lives, yet with year long waits for some people, collaborative efforts between health leadership, advocacy groups and the pharmaceutical industry are required.”

The marketing campaign’s supporting report, 1,000 voices, not 1, highlights quite a few stark findings from a survey of over 1,000 people with cancer throughout the UK.

People from ethnic teams had been extra seemingly to attribute their symptoms to different circumstances (51 per cent vs 31 per cent) and never take their symptoms significantly (34 per cent vs 21 per cent), in contrast with white people, the information exhibits.

They are additionally extra seemingly to expertise issue seeing a GP in contrast to white people, each when it comes to getting an appointment (25 per cent vs 16 per cent) — together with due to long wait instances and few slots being out there — and in having the ability to find time for it due to work (18 per cent vs 4 per cent).

A better proportion of people from minority ethnic teams fear about losing NHS time and sources (52 per cent vs 42 per cent) and are not looking for to be seen as losing their GP’s time (32 per cent vs 18 per cent), in contrast with white people.

Delayed between cancer prognosis and remedy might increase the chance of dying by round 10 per cent.

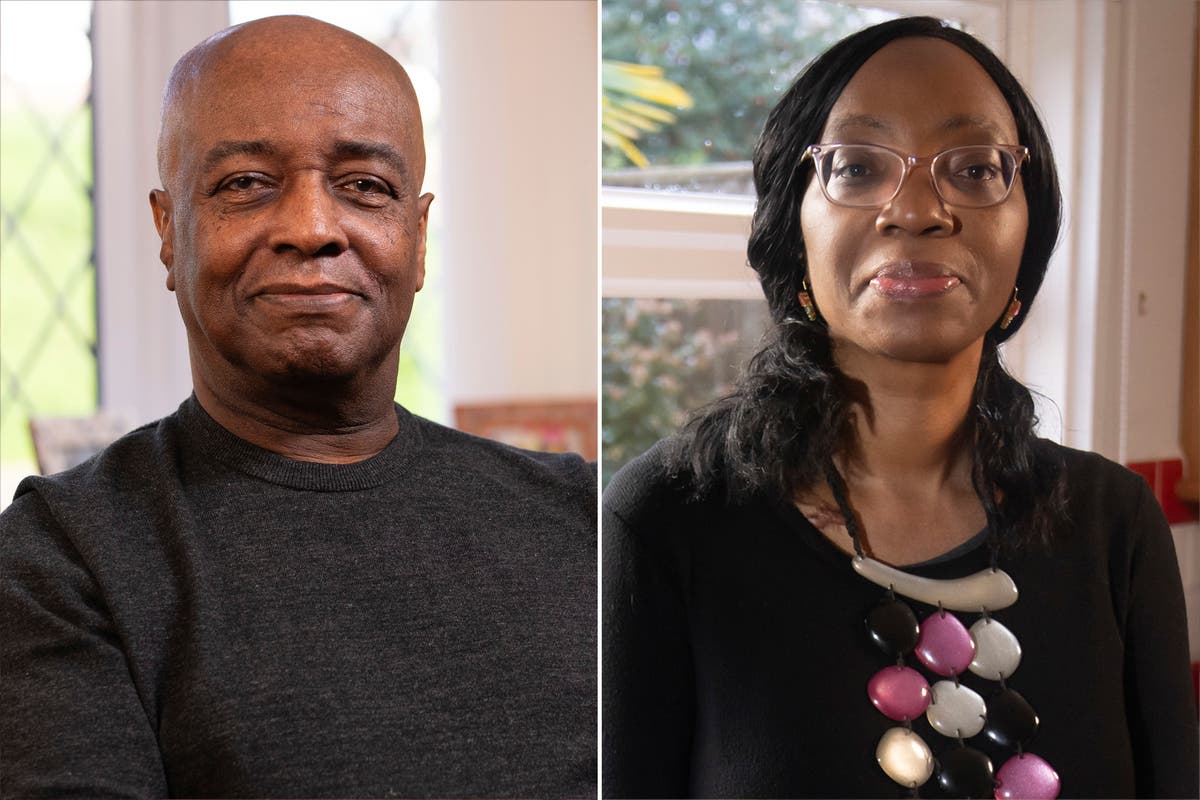

Simeon Green, 60, was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2015, on the age of 49, over a 12 months after first experiencing symptoms.

Unable to declare advantages, and on the similar time supporting his associate who had been diagnosed with breast cancer six months earlier, the pair ended up promoting their belongings so as to maintain a roof over their heads.

The Wolverhampton resident’s compromised eligibility to dwell and obtain free remedy within the UK meant he was unable to declare advantages and risked having to spend £42,000 for his cancer remedy.

At the identical time, Mr Green was preventing deportation as he was caught up within the Windrush scandal and accused of not having correct documentation.

Speaking to The Independent, Mr Green, who’s nonetheless awaiting compensation from the Home Office, mentioned: “Black men are more likely to develop prostate cancer and younger; these risks are often ignored by healthcare practitioners and this leads to more deaths.

“When I received my diagnosis, I ended up planning my funeral because I felt sure I was going to die. On top of this battle, I was living in fear every time the door knocked – that was a part of my life – and feeling scared that the Home Office was going to drag me off to a detention centre for deportation. This dragged on for nine years and a day.”

Mr Green, who runs a help group for different Black males affected by cancer, added: “We’ve seen NHS campaigns about prostate cancer and how it generally affects men, but the heightened risk that Black men face isn’t often highlighted.

“Another problem is the lack of trust in doctors within our communities, plus the lack of Black men being invited to participate in clinical trials.

The study coincides with the launch of a new campaign, Cancer Equals, which is geared towards helping to “understand and help address the many possible reasons for inequalities in Britons’ experiences of cancer”.

According to analysis, causes for delays in diagnoses embody challenges accessing providers, healthcare practitioners not taking sufferers’ symptoms significantly and low consciousness of cancer symptoms.

Precious, a 45-year-old British lady of Nigerian heritage residing in North London, can personally attest to low consciousness about cancer and docs dismissing warning indicators.

She acquired her prognosis in A&E after collapsing in a prepare station following a number of GP appointments by which her symptoms had been put down to stress.

“I had all the symptoms for four months and I’ve been to the GP several times – she kept saying I was stressed and put me on medication. So in my wildest dreams, I didn’t expect the word cancer to come up.”

Prior to her prognosis with continual myeloid leukaemia, on the age of 33, Precious didn’t know a lot about cancer and its related symptoms; it was by no means spoken about inside her household and was thought-about “shameful”.

“In my culture, sometimes people say sickness is a consequence of not doing something right or it being a curse from God for not living a good life; someone suggested it may have been because I didn’t pay my tithes in church,” Precious informed The Independent.

Shortly after her prognosis, Precious was astounded by a care assistant’s suggestion that cancer might have come about as a results of somebody working black magic on her.

“One time I was in hospital, my tummy was hurting really bad and they sent me for an x ray,” she defined.

“A fellow Nigerian woman, a care assistant who learned I’d recently returned from a trip to Nigeria, accompanied me to the X-ray and said: “Sometimes if you steal somebody’s money or land or husband, they can throw Obeah at you and it doesn’t matter what part of the world you’re in, it will hit you’.”

“If you have multiple people, a collective group of people thinking that way, there’s no way that you’re going to want to open up about your cancer,” she added.

Both Mr Green and Precious now work to help people who have had a cancer prognosis and lift consciousness in regards to the illness’s prevalence.

Precious believes strongly in sharing her story to assist different people, particularly these from cultures that don’t usually talk about cancer, to really feel protected and empowered to get the assistance that they want.

“If I can help at least one person, then it’ll be worth it,” she mentioned.

[ad_2]

Source hyperlink