[ad_1]

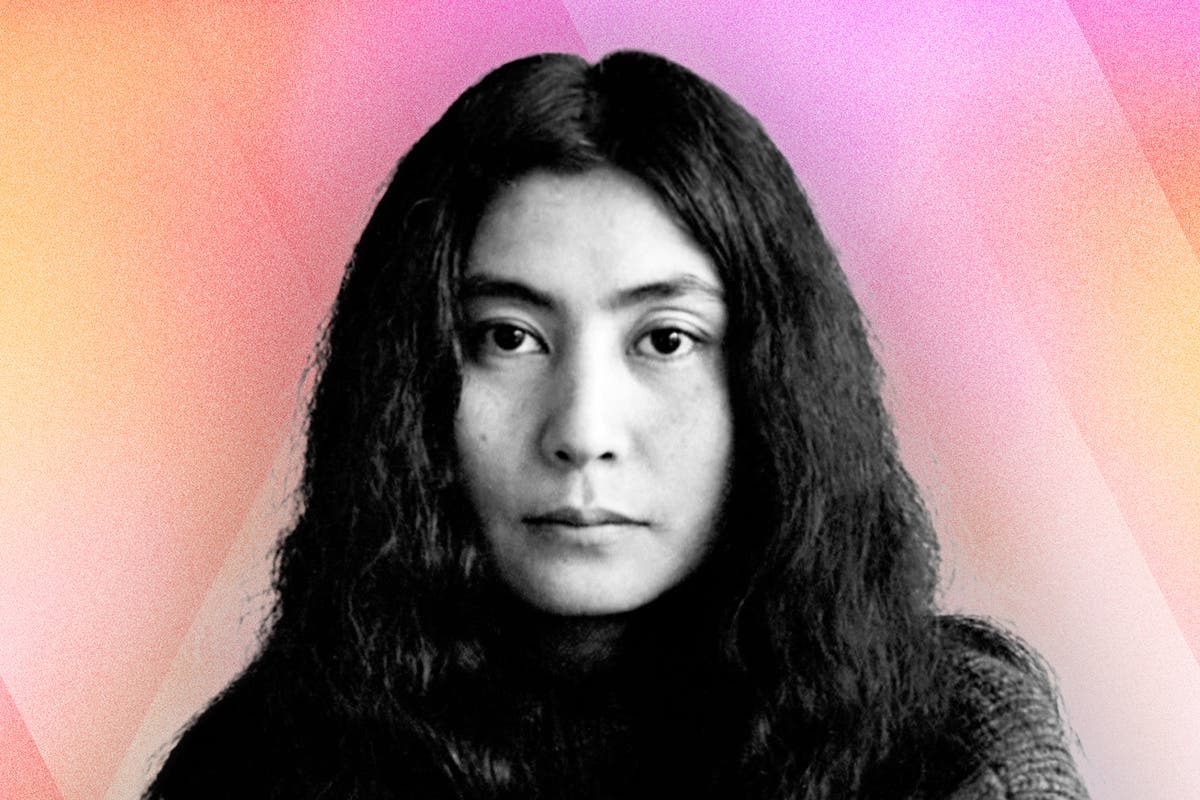

Misunderstood genius or pretentious charlatan? Revolutionary artist or (frankly horrible) singer? Almost six a long time after she turned globally (in)well-known, it’s nonetheless exhausting to discover a cultural determine extra polarising than 90-year-old Yoko Ono. Her relationship with John Lennon is cited as the blueprint of the meddling girlfriend, ruining her associate’s (superior) artwork, her work usually derided and used as a punchline: nobody actually needs to listen to themselves described as “a bit of a Yoko”.

But Peter Jackson’s seven-hour Beatles documentary Get Back, launched in 2021, began to unpick the myths surrounding Ono and the break-up of the world’s largest band. Yes, she’s virtually omnipresent as The Beatles are at work, however she hardly looks like an impediment to their artistic course of; most of the time she’s knitting or studying the newspaper. Now a new exhibition at Tate Modern, the UK’s largest ever showcase of Ono’s work, will additional problem what we predict we find out about her when it opens this month. It’s all a part of an overdue reappraisal, forcing us to ask: how a lot do we actually find out about Yoko Ono? And is it time we began taking her work severely?

Born in 1933, Ono had a privileged upbringing. Both her dad and mom’ households had made their fortunes in banking, and her father’s high-flying job meant that Yoko spent her childhood between Japan and America, observing each cultures as if from a distance. In the aftermath of the devastating air raid on Tokyo in 1945, meals was scarce for everybody, and the Onos discovered themselves buying and selling heirlooms for one thing to eat. Yoko would later pinpoint this as the awakening of her inventive creativeness. Aged 12, she would attempt to distract her youthful brother Keisuke from his starvation by serving to him dream up a fantasy menu. “So we had our conceptual dinner and this [was] maybe my first piece of art,” she instructed The Guardian.

She channelled that early creativity whereas learning at Sarah Lawrence, the progressive liberal arts faculty in New York, laying the foundations of her distinctive model of multi-disciplinary artwork. Often noticed scribbling in an apple tree, Ono began to write down her first “instruction pieces”, temporary, poetic instructions telling the reader to create their very own artwork, both actually or utilizing their creativeness. She’d ultimately compile over 150 of those items in Grapefruit, her 1964 ebook. Music was one other supply of solace: Ono had been classically educated in piano and opera, however discovered herself creating extra avant-garde tastes. A instructor pointed her in the path of John Cage, the radical composer at the forefront of New York’s experimental music scene. He’d quickly turn out to be a frequent collaborator, and a part of Ono’s social circle: in 1956, Ono married the pianist Toshi Ichiyanagi, one among Cage’s proteges.

It wasn’t lengthy earlier than Ono dropped out of faculty and immersed herself in New York’s artwork milieu, hanging out with the artist collective often known as Fluxus. The group unravelled the boundaries between artwork and actual life; they had been extra involved with staging occasions that combined poetry, music and efficiency than creating conventional artwork objects. Fluxus needed to place the viewers at the coronary heart of their work – Ono’s 1964 efficiency “Cut Piece” did precisely that, and received her recognition as a reputation to look at, too. Dressed in her finest outfit, the then 31-year-old stood on stage at the Yamaichi Concert Hall in Kyoto, Japan; viewers members had been invited to step up and reduce away her garments with scissors. They began off with small, virtually well mannered, snips, earlier than turning into emboldened, chopping at the artist’s bra straps. Their actions felt transgressive, virtually violent. Ono introduced “Cut Piece” to New York’s Carnegie Recital Hall the following 12 months; it’s been interpreted variously as a feminist commentary, an exploration of the relationship between artist and viewers, or an allusion to the bombing of Japan throughout World War II.

By 1966, Ono was a big participant in the up to date artwork world, well-known sufficient to launch a solo present at London’s Indica Gallery, an area at the coronary heart of the capital’s counter-cultural scene (today, its web site is occupied by a department of White Cube, one other scenester-y gallery). This would set the stage for her assembly with John Lennon. Invited alongside to Ono’s exhibition preview, he was instantly struck by one explicit piece. After climbing up a ladder, Lennon discovered a magnifying glass connected to a canvas, then used it to learn the tiny phrase Ono had written onto it: “YES”. Its positivity received him over, he later defined throughout an look on The Mike Douglas Show: “In those days most art put everybody down, got people upset.”

Newlyweds: Ono and Lennon on their honeymoon in Paris in 1969

(Getty Images)

Lennon didn’t initially endear himself to Ono, taking a chew out of an apple she had positioned on a pedestal (and deliberate to promote for £200). But he in any other case appeared to shortly grasp her conceptual work. Observing one among her instruction work, which invited viewers to hammer a nail right into a clean canvas, he requested if he might give it a go; Ono demurred, noting that the exhibition hadn’t opened to the public but, earlier than asking him to pay 5 shillings for the privilege. “So smart-ass here says, ‘Well, I’ll give you an imaginary five shillings and hammer an imaginary nail in,’” Lennon later instructed Playboy. “And that’s when we really met. That’s when we locked eyes and she got it and I got it and that was it.” Like an avant-garde Richard Curtis movie (besides each protagonists had been married: Lennon to Cynthia, and Ono to her second husband, musician Anthony Cox).

Shortly after that first encounter, Ono apparently turned up at The Beatles’ Savile Row workplace unannounced. Lennon wasn’t there, Craig Brown writes in his ebook One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time. Ringo Starr was, although, “so she directed herself at him instead, and began to recount her philosophy of art and life”, Brown claims. “Unfortunately, Ringo couldn’t decipher a word she was saying, and exited as fast as his legs could carry.” Brown paints a beautiful scene: you possibly can simply image Ringo’s hangdog expression as he politely nods his method by an impenetrable monologue, planning easy methods to do a runner. But it’s not significantly charitable to both Starr (at all times the band’s resident punchline) or to Ono, dialling up her self-seriousness and her obvious desperation to affix The Beatles’ inside circle.

Brown goes on to think about how Ringo might need influenced Ono’s poetry: “Carry a heavy object up a hill. But not for too long, or it’ll do your back in.” Ono’s artwork is sort of too simple to mock. “Carry a bag of peas,” one among her instruction poems implores. “Leave a pea wherever you go.” Another invitations us to “imagine a thousand suns in the sky shining at the same time; let them shine for one hour; then, let them gradually melt into the sky.” How poetic. And wait, it’s not completed but. “Make one tuna fish sandwich and eat.” Detractors might (and, let’s face it, do) declare that that is simply, properly, gibberish: the kind of sentiment higher suited to a very spaced-out line of fridge magnets. Her Twitter/X account is a very simple goal: a few decade in the past, Andy Murray’s mom Judy went by a part of snarkily replying to the self-help maxims that Ono had posted (and being gleefully praised in newspapers for doing so).

Conceptual: Ono at an exhibition of her work in 1968

(Getty Images)

But we shouldn’t write off Ono’s work as Pollyanna-ish and sunny, allotting greetings card truisms. Think of “Cut Piece” and the method it attracts out the viewers’s atavistic impulses. Or her “Rape” movie, recorded in 1969, wherein the digital camera follows a mannequin to her house, watching her turn out to be much less and fewer comfy with its intrusion; or “Fly”, the 1970 movie wherein the digital camera is educated on an insect buzzing over a woman’s bare physique; it’s by no means made fully clear whether or not she is sleeping or a corpse. “This whole idea of a male society was based on the fact that women shut up… but shutting up is death in a way,” she defined, “So we were always kind of pretending to be dead.” There are nonetheless loads of Beatles followers who would quite that Ono had “shut up” and left their idol properly alone. Lennon’s break-up from his spouse Cynthia was definitely messy and even merciless; it didn’t precisely cowl him and Ono in glory. But does that make her deserving of her standing as a cultural hate determine, alternately mocked and despised?

By the time that she and John had been in a relationship, there have been apparent fault traces in The Beatles already. Their supervisor Brian Epstein, who’d been in a position to steadiness their varied personalities so properly, had died in 1967. Lennon, McCartney and Harrison had been all griping about artistic management. But it’s Yoko’s title that’s at all times cited as the band’s demise knell; she’s been depicted as a meddler, putting a wedge between Lennon and McCartney, luring the former away to work on experimental music initiatives and lie in mattress making pronouncements about peace. It is, in fact, awkward and irritating when your pal’s new associate turns up at each social occasion (no marvel George Harrison apparently turned embroiled in a shouting match with Lennon after Ono ate one among his digestive biscuits with out his permission). But Peter Jackson’s Get Back documentary, which charts the 1969 recording of Let It Be, reveals Ono as an odd however largely disengaged presence; there’s little signal of interfering.

When the band disintegrated, and Lennon and Ono began to supply extra music and artwork collectively, a few of the criticism was simply par for the course, the kind of factor you count on if you’re placing your artistic work and concepts out into the world. Were their requires peace an oversimplification, virtually infantile? Was a few of Yoko’s singing… a bit screamy? Why had been they being photographed posing in large luggage? But a lot of the anti-Yoko vitriol was shot by with blatant racism. Before Lennon, Ono would later say, she “was living as an artist and had relative freedom as a woman, and was considered a bitch in this society”; after she met John, she “was upgraded into a witch … considered an ugly woman, an ugly Jap, for taking away your monument”. Lennon later claimed that the couple determined to depart England so as to get away from the tabloids’ xenophobia, however issues weren’t a lot better in the American press: a 1970 interview with Ono was revealed in Esquire underneath the nasty headline “John Rennon’s Excrusive Gloopie”.

Reappraisal: a retrospective of Ono’s work opened at MoMa in 2015

(Getty Images)

Both Ono and Lennon took an prolonged hiatus from recording after the delivery of their son, Sean, in 1975; 5 years later, they might staff up once more for the album Double Fantasy in 1980, its observe itemizing alternating between the two of them, like a dialogue. It was meant as Lennon’s comeback, however would finish up being his ultimate work: on 8 December, three weeks after Double Fantasy’s launch, he was shot and killed exterior the couple’s Manhattan residence constructing.

“Around the time of John’s passing, I really felt that I had an almost uncontrollable anger in me,” Ono has stated. “And I felt that I really needed to do something about it. Otherwise it would eat me up. I felt a desperate need to transform that energy into creativity.” She launched the idea album Starpeace, meant as a rejoinder to President Reagan’s plans for a missile defence system, in 1985, which turned her most profitable solo effort; the identical 12 months, she opened the Strawberry Fields Memorial in Central Park, not removed from her New York house (she remained at her and Lennon’s residence at the Dakota Building till only a few years in the past, when she reportedly decamped to a 600-acre farm in the Catskills).

A slew of Ono retrospectives adopted in the ensuing a long time, together with one at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the place she had beforehand staged an unauthorised present again in 1971, protesting towards the lack of ladies artists of their assortment (that “exhibition” consisted of a bunch of perfumed flies that she had launched into the gallery area). She has since collaborated with youthful musicians influenced by her work, from Peaches to The Flaming Lips to Lady Gaga, and doubled down on her activism too, founding the LennonOno Grant for Peace, given to artists in conflict zones, and protesting towards fracking.

Her present at the Tate Modern will deliver her work to a brand new viewers, a lot of whom will likely have their very own preconceptions about Ono. It may not win all of them over – however no matter you consider Yoko, she is definitely resilient in the face of criticism, and worse. “Understand that nobody can deter you, nobody can intimidate you, nobody can stop you, except yourself,” she says. “You just have to remember that.”

Yoko Ono: MUSIC OF THE MIND is at Tate Modern from 15 February to 1 September

[ad_2]

Source hyperlink