[ad_1]

Your help helps us to inform the story

From reproductive rights to local weather change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the bottom when the story is creating. Whether it is investigating the financials of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our newest documentary, ‘The A Word’, which shines a mild on the American girls combating for reproductive rights, we all know how vital it’s to parse out the details from the messaging.

At such a vital second in US historical past, we’d like reporters on the bottom. Your donation permits us to maintain sending journalists to communicate to either side of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans throughout your complete political spectrum. And not like many different high quality information retailers, we select not to lock Americans out of our reporting and evaluation with paywalls. We imagine high quality journalism ought to be obtainable to everybody, paid for by those that can afford it.

Your help makes all of the distinction.

As a lot because the superstars love their followers, followers are predators.” So mentioned the late Dr Donna Rockwell, a scientific psychologist and one of many world’s main consultants on fame and celebrity, throughout an interview with The Face in 2019. “In a way [fame is] almost like an excommunication because now you are an object. People are watching you.”

Her phrases had been an eerie foreshadowing of a sentiment lately expressed by Chappell Roan, the American singer who shot to stratospheric fame this 12 months. “If you saw a random woman on the street, would you yell at her from your car window? Would you harass her in public?” Roan mentioned in a social media video calling out followers’ behaviour in August. “Would you stalk her family? Would you follow her around? Would you try to dissect her life and bully her online?”

In the uncooked, unfiltered publish, Roan railed in opposition to such “weird” behaviour, calling it “creepy”: “I don’t care that this crazy type of behaviour comes along with the job, the career field I’ve chosen. That does not make it OK, that doesn’t make it normal.” The diatribe cut up opinion – some praised her for setting boundaries, others poured scorn for what they perceived as a impolite and entitled outburst – and even garnered sufficient consideration to be parodied in a Saturday Night Live sketch that includes Bowen Yang dressed as viral hippo Moo Deng. Since then, she’s hit the headlines for telling off a photographer who “yelled” at her at each the VMAs and Olivia Rodrigo’s GUTSWorld Tour movie premiere, incomes the nickname “Chappell Moan!” from some quarters. But her perceived temerity for daring to query the accepted “non-negotiables” of being within the public eye is shining a mild on the, at instances, distinctly unpalatable actuality of being a celebrity.

Though her personal trajectory from comparatively under-the-radar artist to Gen Z celebrity has been whiplash-inducingly quick, Roan will not be the primary to draw consideration to the pitfalls of “parasocial” relationships. This time period describes a one-sided reference to a celebrity or public determine – one through which the well-known celebration is totally oblivious to the “connection”.

Actor and singer Keke Palmer shared a troubling expertise with a fan in 2022, whereby they began filming her in opposition to her needs. “No means no, even when it doesn’t pertain to sex,” she tweeted.

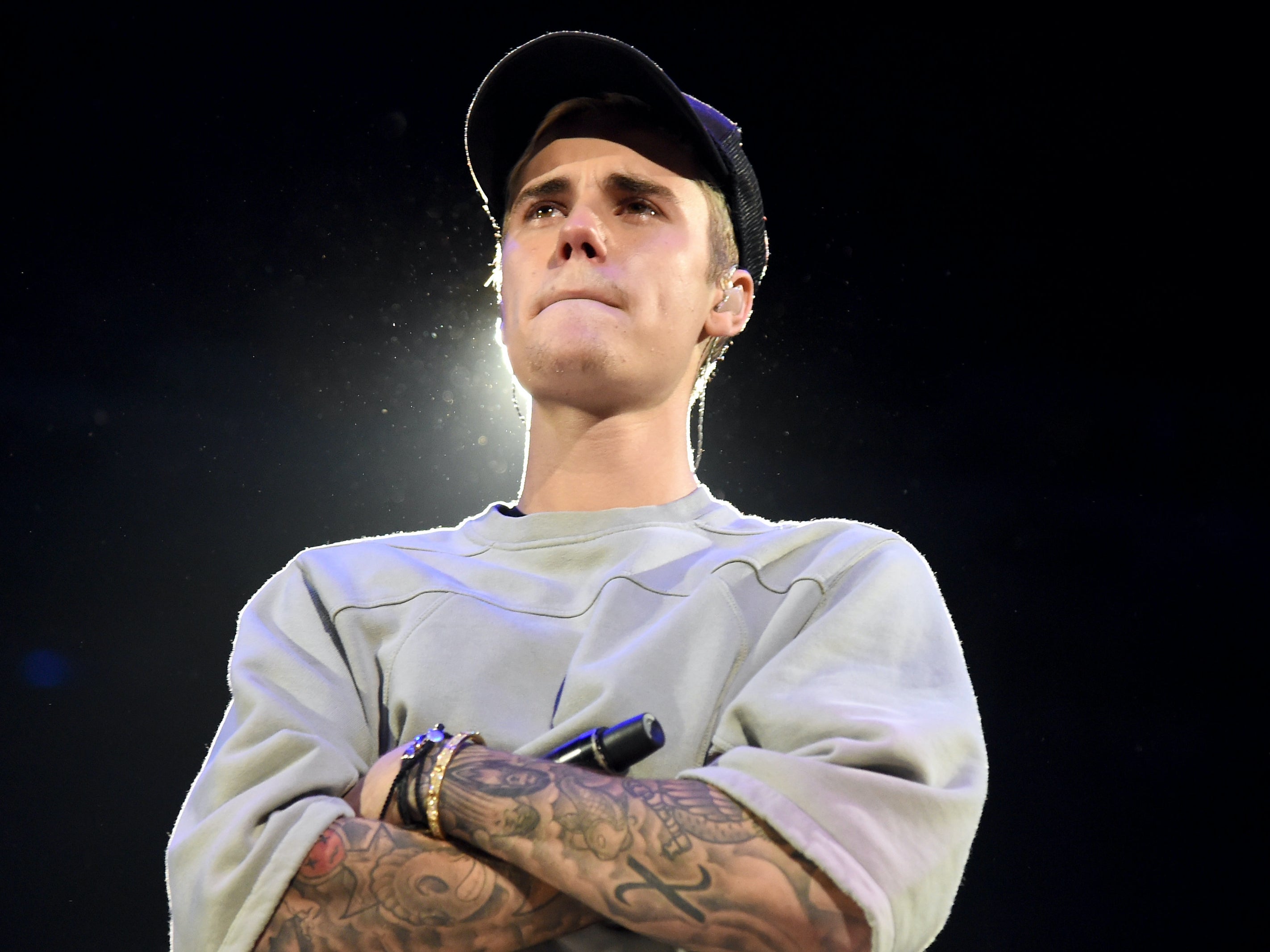

Popstar Justin Bieber took the choice in 2016 to flip down photograph requests from followers. “It has gotten to the point that people won’t even say hi to me or recognise me as a human,” he defined in an Instagram publish. “I want to be able to keep my sanity.” That similar 12 months, actor Jennifer Lawrence outlined why she had additionally began turning down selfies: “I think that people think that we already are friends because I am famous and they feel like they already know me – but I don’t know them. I have to protect my bubble.”

While the trendy notion of celebrity is credited with having its earliest roots within the late nineteenth century, the web and social media have essentially altered the character of fame within the final decade or so. There has all the time been a darker facet to the flicker of hitting the large time – a difficulty that’s poignantly explored in a forthcoming BBC documentary, Boybands Forever, on Nineties teams. The distinction is that Roan and her ilk aren’t retrospectively wanting again and reflecting on the insanity, however brazenly talking about it in actual time, whereas their star remains to be on the ascent.

The further challenges of navigating celebrity within the digital age are additionally extra obvious than ever: “fans” more and more feeling like they’ve possession over the thing of their obsession; the psychological well being implications of in a single day or overwhelming fame; the scrutiny and subsequent cancel tradition inherent in reaching never-before-possible numbers of individuals through social media.

Dr David Giles, a reader in media psychology on the University of Winchester who’s written extensively about fame in his two books, Illusions of Immortality and Twenty-First Century Celebrity, tells me that the panorama is altering due to media and technological change.

“One of the things I often talk about is the importance of the medium, and the affordances of that medium,” he says. “Twitter/X affords something quite different from TV/radio. If you’ve grown up with social media and are used to negotiating lots of followers you can probably tolerate small increases in your fame, but suddenly having to deal with thousands of followers is a different matter. So even ‘social media natives’ can struggle with the increasing demands – you get used to a particular rhythm of communication and then it all changes, and you’re getting different types of communication (abuse, etc) and you have to have a plan to deal with it.”

Online abuse, he theorises, is commonly “opportunistic”, as a result of “people still can’t quite believe they’ve got this level of access to celebrities.” Think about it: previously, a well-known actor was distant, unattainable. You’d see them on the large display screen, or gracing the pages of a journal; the one manner you’d expertise any sort of interplay was by writing a letter to their “team” that they could or could not learn, or queuing for hours at a movie premiere within the useless hope of nabbing an autograph.

Someone working in a conventional area like pop music doesn’t have the safety that the trade used to present

Dr David Giles, reader in media psychology

In 2024, the panorama has modified dramatically. If your most popular celeb has any sort of social media presence, you’ve got entry to much more of their lives, together with intimate components – possibly they’ve shared a video of themselves playing around of their house, or footage of their youngsters. You can talk with them instantly through feedback; they could even reply or retweet you. There’s a higher sense than ever of figuring out this particular person.

“If people have access to what feels like a private part of a celebrity’s life, like their kitchen or their children or their garden or their hobbies, then they have a sense of familiarity with the celebrity,” agrees Nicholas Rose, a psychotherapist who counts performers and high-profile people amongst his shoppers. “So they have a sense of a relationship, which won’t be shared, it won’t be being in a relationship. That causes confusion – they feel that they can just walk up to a celebrity and speak to them.”

It’s not the one side of up to date celebrity that appears deeply unappealing. Traditionally, celebrities had been shielded from their public by a number of layers of gatekeepers relying on the trade – document corporations, TV channels, managers, heavies – a few of which may really be seen as a burden, stifling creativity. Now, social media permits customers to reduce by means of these layers and communicate instantly to followers – however this unfettered entry has its shadow facet. “Someone working in a traditional field like pop music doesn’t really have the protection that the industry used to provide,” says Giles. “Elvis could be smuggled out of the venue by his minders and safely deposited in a hotel, but today he would still be sharing his online space with his fans and whoever wants to insult him.”

Unlike previously, when a celebrity would know once they had been “on” and once they had been “off” responsibility, fashionable life additionally sees a big blurring of the non-public {and professional} spheres. “As we move to an online world it’s harder to have those breaks between our internal and private life and our external and public life,” provides Rose. “Doing celebrity is different from being celebrity; it’s a bit like any job that you have to get into the mindset for. It’s about that separation.”

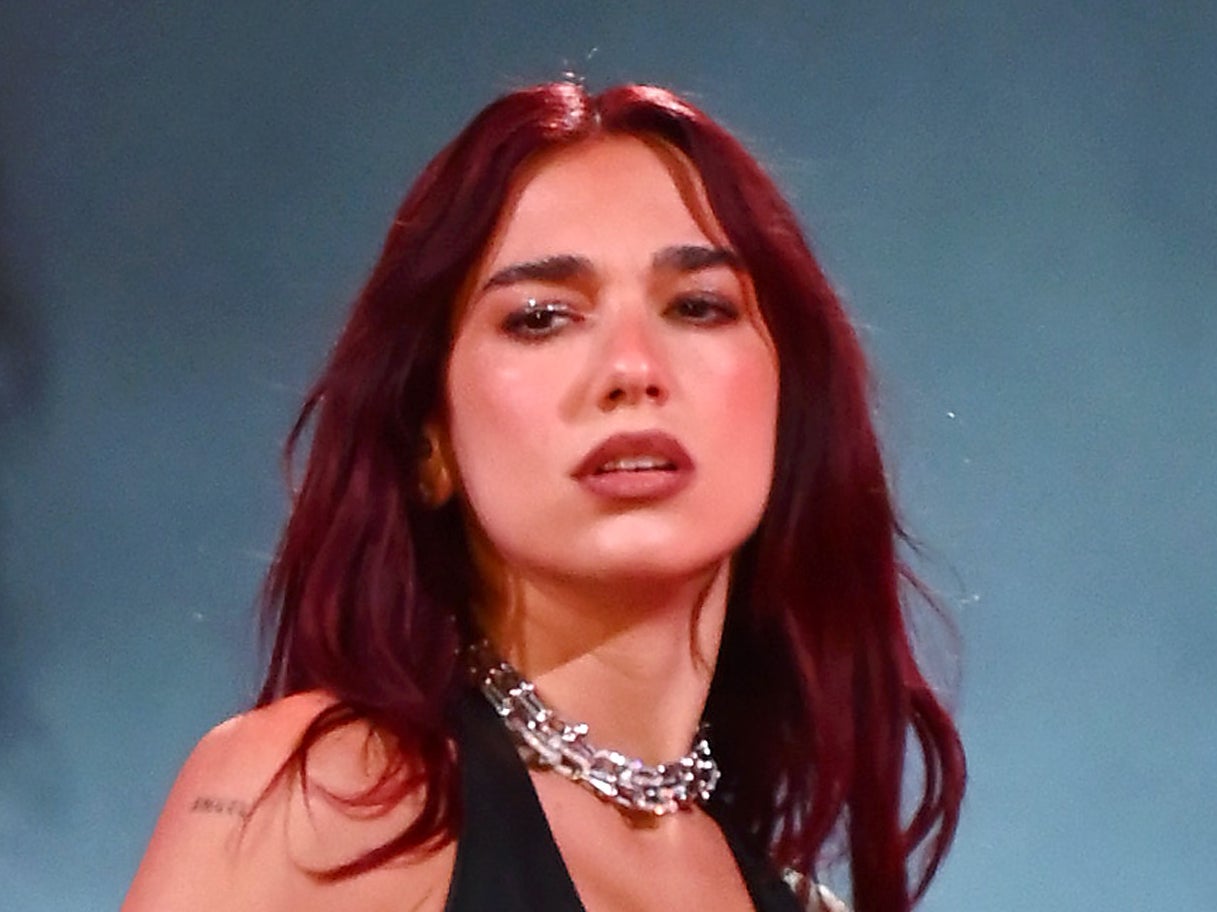

And separation is hard while you’re simply out and about, residing your life, but get accosted at each flip – and roundly criticised in case you don’t really feel like taking a image with a stranger that day, as Dua Lipa discovered when she was on vacation together with her household. (She was accused of being “rude” regardless of turning down the request, videoed and shared on-line, with commendable grace.) Not to point out getting pounced on backstage at Glastonbury and filmed whereas pressured to pay attention to somebody’s cringe-making unique track…

In a research entitled “Being a Celebrity: A Phenomenology of Fame”, Rockwell and Giles recognized 4 distinct psychological phases of fame that individuals undergo: love/hate, dependancy, acceptance and, lastly, adaptation.

Roan is clearly in her love/hate part (emphasis on the “hate”) however after learning the lives of 15 US celebrities throughout a vary of industries, Rockwell and Giles concluded that this often strikes onto “addiction”. Celebrities begin craving the eye they’ve turn out to be used to – “Behaviour is directed solely towards the goal of remaining famous,” claims the research. Participants described the sensation as a “high”; one admitted: “I’ve been addicted to almost every substance known to man at one point or another, and the most addictive of them all is fame.”

Next comes an acceptance part, requiring the celebrity to get used to all features of fame, together with these which can be adverse, “as the attention becomes overwhelming and expectations, temptations, mistrust, and familial concerns come to the fore”.

Fame is nice till you get an excessive amount of of a good factor

Gayle Stever, behavioural sciences professor

Finally, there’s adaptation. The particular person essentially adjustments their routines and behaviours to address the brand new regular, together with – as in Bieber and Lawrence’s instances – implementing strict boundaries when it comes to followers. “Once you’re famous, you don’t make eye contact or you keep walking… you just don’t hear [people calling your name],” mentioned one research participant.

It’s not simply a particular person’s behaviour that adjustments with mega-stardom – their mind chemistry adjustments too. “The sad part of the adaptation is that if you are famous, your brain becomes accustomed to all of that attention, that adoration and all of those eyes on you,” mentioned Rockwell. Serotonin, endorphins and dopamine – the triumvirate of feel-good chemical compounds – can be launched once we obtain optimistic affirmation, reminiscent of a whole lot of hundreds of likes on social media, or followers chanting in adoration. “Your neurons get used to a certain level of excitation and stimulation. And then, forevermore, you kind of want it to be at that level.”

Despite the entire above, there are clearly upsides. Otherwise, why would so many people be bewitched by the thought of buying fame? And bewitched we’re, proper from childhood – a 2012 research discovered that “fame” was the most important aim for youngsters aged between 10 and 12 within the US, whereas, in accordance to a 2019 survey of British youngsters, “YouTuber” was probably the most fascinating future occupation.

In her guide The Psychology of Celebrity, social and behavioural sciences professor Gayle Stever requested a number of actors in regards to the psychological impacts of fame. “They each felt that the fame they had gained was mostly positive in their own lives and mostly positive in the lives of those around them,” she says. “I think most people are able to deal with at least the moderate levels of fame that are more common … Perhaps the best answer is that fame is good until you get too much of a good thing.”

It’s this exact stage of celebrity that may be difficult to navigate – not everybody goes to be Taylor Swift, positive, however fame is a fickle beast, one thing which will at first be courted however then can not essentially be managed.

The influence this could have – in addition to the stress related to having to keep on the high of your skilled recreation to stay feted – can lead to a higher dependence on coping methods, each wholesome and unhealthy. Rose says a notably efficient software for his celebrity shoppers is non secular practices, whether or not organised faith, yoga or meditation. At the opposite finish of the spectrum, although, is substance abuse: “There can be more reliance on alcohol, for example, or drugs.”

It’s a darkish and devastating trajectory that has claimed a disproportionately excessive variety of well-known folks’s lives, from Heath Ledger and Amy Winehouse to, most lately, Liam Payne, who tragically fell to his dying from a lodge balcony in Buenos Aires, aged simply 31, whereas reportedly intoxicated. The former One Direction band member turned solo artist had spoken typically about his struggles with fame and subsequent alcohol abuse, having all of the sudden been thrust into the position of a world celebrity on the age of simply 16. He known as celebrity “a little bit toxic”, and mentioned of on-line trolling: “There’s times where that level of loneliness and people getting into you every day every so often … that’s almost nearly killed me a couple of times.” But stepping off the popstar treadmill was simpler mentioned than performed: “Once you start, you can’t really press the stop button,” he as soon as advised The Guardian.

The media frenzy and limitless hypothesis surrounding his dying solely lends credence to this evaluation. As Little Mix singer Perrie Edwards put it: “There are no consequences for people’s comments online. People are not looked after enough in this industry, people are put on a pedestal. They are treated like a god and then everyone jumps on this bandwagon of like ‘let’s tear them down’. But people are human.”

It all paints a image of fame as one thing to be averted, slightly than aspired in direction of; a state of being that’s damaging, slightly than fascinating. Is the aim of reaching celebrity lastly shedding its lustre? That stays to be seen. But the celebrity recreation definitely appears to have turn out to be one the place, the extra you win, the extra you lose.

[ad_2]

Source hyperlink