[ad_1]

Your help helps us to inform the story

This election continues to be a useless warmth, in keeping with most polls. In a combat with such wafer-thin margins, we’d like reporters on the bottom speaking to the individuals Trump and Harris are courting. Your help permits us to maintain sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from throughout the complete political spectrum each month. Unlike many different high quality information shops, we select to not lock you out of our reporting and evaluation with paywalls. But high quality journalism should nonetheless be paid for.

Help us maintain deliver these crucial tales to gentle. Your help makes all of the distinction.

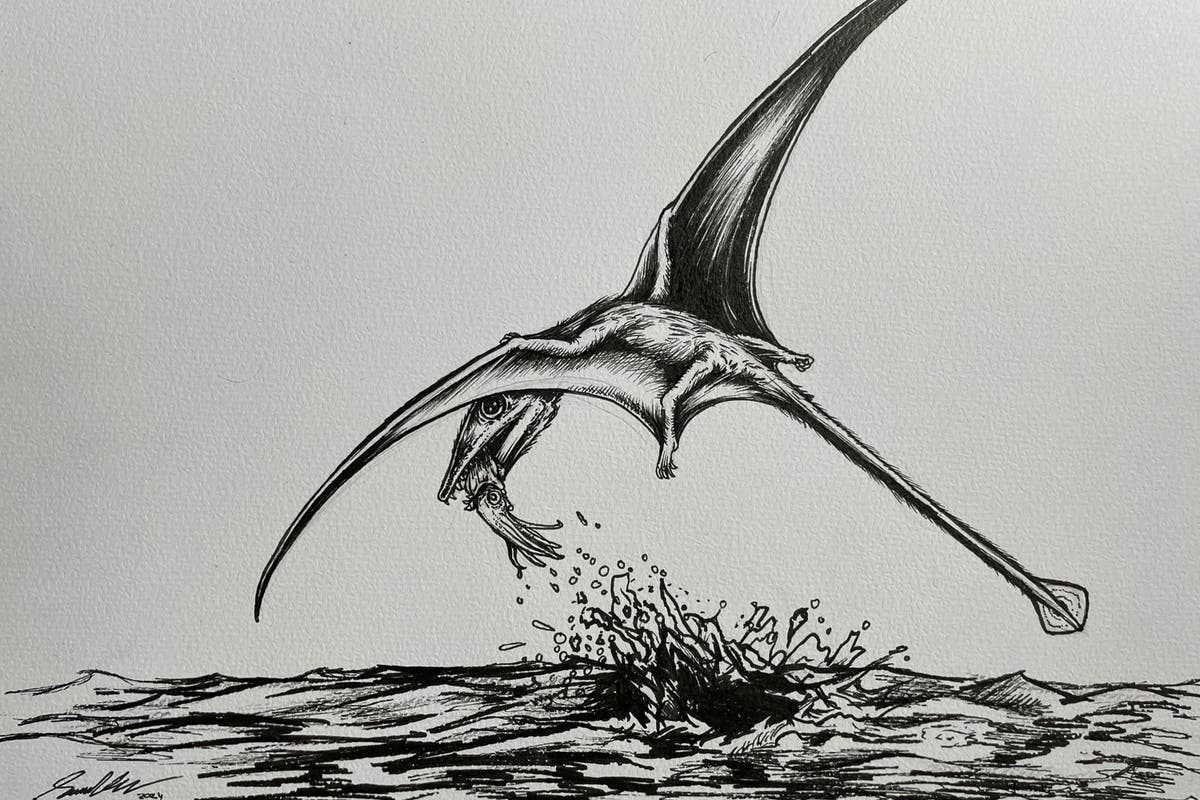

Scientists have discovered that prehistoric flying reptiles that lived 182 million years in the past lived on a diet of small fish and squid.

The “first-ever discovery” of the fossilised abdomen contents of pterosaurs has led to a singular glimpse into the feeding habits of the enormous species, which had wingspans of as much as 12 metres (39ft).

The findings, printed within the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, have been made by scientists from the University of Portsmouth and the Staatliches Museum fur Naturkunde Stuttgart (SMNS) in Germany.

The workforce had analysed the fossilised abdomen contents of two pterosaur species, dorygnathus and campylognathoides, from the early Jurassic interval, present in modern-day south-west Germany.

They discovered that dorygnathus ate small fish for its final meal whereas campylognathoides ate prehistoric squid.

Dr Roy Smith, from the University of Portsmouth’s School of Environment and Life Sciences, stated: “It is incredibly rare to find 180 million-year-old pterosaurs preserved with their stomach contents, and provides ‘smoking gun’ evidence for pterosaur diets.

“The discovery offers a unique and fascinating glimpse into how these ancient creatures lived, what they ate, and the ecosystems they thrived in millions of years ago.”

Dr Samuel Cooper, additionally from the University of Portsmouth, stated: “The fossilised stomach contents tell us a lot about the ecosystem at that time and how the animals interacted with each other.

“For me, this evidence of squid remains in the stomach of campylognathoides is therefore particularly exciting.

“Until now, we tended to assume that it fed on fish, similar to dorygnathus, in which we found small fish bones as stomach contents.

“The fact that these two pterosaur species ate different prey shows that they were likely specialised for different diets.

“This allowed dorygnathus and campylognathoides to coexist in the same habitat without much competition for food between the two species.”

[ad_2]

Source hyperlink