[ad_1]

Warnings about deepfakes and disinformation fueled by synthetic intelligence. Concerns about campaigns and candidates utilizing social media to unfold lies about elections. Fears that tech firms will fail to deal with these points as their platforms are used to undermine democracy forward of pivotal elections.

Those are the troubles dealing with elections in the U.S., the place most voters converse English. But for languages like Spanish, or in dozens of countries the place English is not the dominant language, there are even fewer safeguards in place to guard voters and democracy towards the corrosive results of election misinformation. It’s a problem getting renewed attention in an election yr in which more individuals than ever will go to the polls.

Tech firms have confronted intense political stress in nations just like the U.S. and locations just like the European Union to point out they’re critical about tackling the baseless claims, hate speech and authoritarian propaganda that pollutes their websites. But critics say they have been much less conscious of comparable considerations from smaller nations or from voters who converse different languages, reflecting a longtime bias towards English, the U.S. and different western democracies.

Recent adjustments at tech corporations — content material moderator layoffs and selections to rollback some misinformation insurance policies — have solely compounded the scenario, whilst new applied sciences like synthetic intelligence make it simpler than ever to craft lifelike audio and video that may idiot voters.

These gaps have opened up alternatives for candidates, political events or overseas adversaries trying to create electoral chaos by focusing on non-English audio system — whether or not they’re Latinos in the U.S., or one of many hundreds of thousands of voters in India, as an illustration, who converse a non-English language.

“If there’s a significant population that speaks another language, you can bet there’s going to be disinformation targeting them,” mentioned Randy Abreu, an legal professional on the U.S.-based National Hispanic Media Council, which created the Spanish Language Disinformation Coalition to trace and establish disinformation focusing on Latino voters in the U.S. “The power of artificial intelligence is now making this an even more frightening reality.”

Many of the massive tech firms repeatedly tout their efforts to safeguard elections, and never simply in the U.S. and E.U. This month Meta is launching a service on WhatsApp that may permit customers to flag attainable AI deepfakes for motion by fact-checkers. The service will work in 4 languages — English, Hindi, Tamil and Telugu.

Meta says it has groups monitoring for misinformation in dozens of languages, and the corporate has introduced different election-year insurance policies for AI that may apply globally, together with required labels for deepfakes in addition to labels for political advertisements created utilizing AI. But these guidelines haven’t taken impact and the corporate hasn’t mentioned when they may start enforcement.

The legal guidelines governing social media platforms fluctuate by nation, and critics of tech firms say they’ve been quicker to deal with considerations about misinformation in the U.S. and the E.U., which has lately enacted new lawsdesigned to deal with the problem. Other nations all-too typically get a “cookie cutter” response from tech firms that falls brief, in line with an evaluation printed this month by the Mozilla Foundation.

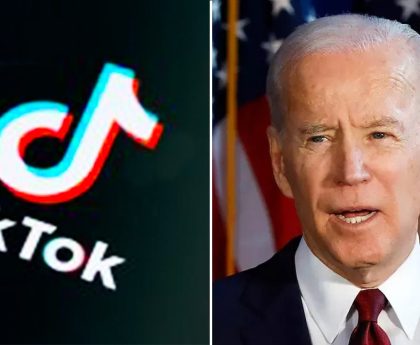

The research checked out 200 totally different coverage bulletins from Meta, TikTok, X and Google (the proprietor of YouTube) and located that just about two-thirds have been targeted on the U.S. or E.U. Actions in these jurisdictions have been additionally more more likely to contain significant investments of employees and sources, the inspiration discovered, whereas new insurance policies in different nations have been more more likely to depend on partnerships with fact-checking organizations and media literacy campaigns.

Odanga Madung, a Nairobi, Kenya-based researcher who carried out Mozilla’s research, mentioned it turned clear that the platforms’ deal with the U.S. and E.U. comes on the expense of the remainder of the world.

“It’s a glaring travesty that platforms blatantly favor the U.S. and Europe with excessive policy coddling and protections, while systematically neglecting” different areas, Madung mentioned.

This lack of deal with different areas and languages will improve the danger that election misinformation might mislead voters and influence the outcomes of elections. Around the globe, the claims are already circulating.

Within the U.S., voters whose major language is one thing different than English are already dealing with a wave of deceptive and baseless claims, Abreau mentioned. Claims focusing on Spanish audio system, as an illustration, embrace posts that overstate the extent of voter fraud or include false details about casting a poll or registering to vote.

Disinformation about elections has surged in Africa forward of current elections, in line with a research this month from the Africa Center for Strategic Studies which recognized dozens of current disinformation campaigns — a four-fold improve from 2022. The false claims included baseless allegations about candidates, false details about voting and narratives that appear designed to undermine assist for the United States and United Nations.

The middle decided that some of the campaigns have been mounted by teams allied with the Kremlin, whereas others have been spearheaded by home political teams.

India, the world’s largest democracy, boasts more than a dozen languages every with more than 10 million native audio system. It additionally has more than 300 million Facebook customers and almost half a billion WhatsApp customers, essentially the most of any nation.

Fact-checking organizations have emerged because the entrance line of protection towards viral misinformation about elections. The nation will maintain elections later this spring and already voters going surfing to seek out out in regards to the candidates and points are awash in false and deceptive claims.

Among the most recent: video of a politician’s speech that was rigorously edited to take away key traces; years-old images of political rallies handed off as new; and a pretend election calendar that offered the fallacious dates for voting.

An absence of serious steps by tech firms has pressured teams that advocate for voters and free elections to band collectively, mentioned Ritu Kapur, co-founder and managing director of The Quint, an internet publication that lately joined with a number of different shops and Google to create a new fact-checking effort often called Shakti.

“Mis- and disinformation is proliferating at an alarming pace, aided by technology and fueled and funded by those who stand to gain by it,” Kapur said. “The only way to combat the malaise is to join forces.”

[ad_2]

Source hyperlink